Professional Aspirations as Indicators of Responsible Leadership Style and Corporate Social Responsibility. Are We Training the Responsible Managers that Business and Society Need? A Cross-national Study

[Las aspiraciones profesionales como indicadores del estilo de liderazgo responsable y de la responsabilidad social corporativa. ¿Estamos formando a los directivos responsables que necesitan las empresas y la sociedad? Un estudio entre países]

Flor Sánchez, Angélica Sandoval, Jesús Rodríguez-Pomeda, and Fernando Casani

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a5

Received 8 September 2019, Accepted 18 December 2019

Abstract

The relationship between responsible leadership (RL), identified from achievement expectations, and the importance attached to corporate social responsibility (CSR) was analyzed. In a survey of 1,833 business management undergraduates in six Ibero-American countries, factor analysis identified three approaches to stakeholder relations, behaviors, and professional aspirations: a relational style associated with the intention to collaborate with others; a pragmatic style geared to attaining personal and organizational objectives; and an individualist style informed by a drive for personal achievement. Regression analyses confirmed the relationship between relational and pragmatic styles and CSR geared to stakeholder well-being, protection of social and natural environments, and ethical management. Both were associated with regard to the responsibilities that ensure business survival (such as meeting customer needs), while the individualist style was aligned with hostility toward those dimensions of CSR. These findings suggest that the relational and pragmatic styles lead to more effective CSR management.

Resumen

Se analiza la relación entre estilos de liderazgo responsable (LR), éste último identificado a partir de las expectativas profesionales de logro, y la importancia atribuida a la responsabilidad social corporativa (RSC). Contamos con 1,833 participantes de seis países iberoamericanos que cursaban estudios universitarios relacionados con gestión empresarial. Un análisis factorial identificó un estilo de LR relacional orientado a colaborar con otras personas, un estilo pragmático asociado a logros personales y organizacionales y un estilo individualista orientado a intereses personales. Los análisis de regresión mostraron una relación positiva entre los estilos relacional prágmatico y la valoración de la RSC que busca el bienestar de la comunidad, de stakeholders internos y externos, la protección del medioambiente y el comportamiento ético, a la vez que asegura la sostenibilidad de organización, aspectos todos ellos valorados negativamente desde el estiloindividualista. Los datos sugieren que en el contexto socio-económico actual los estilos relacional y pragmático serían más efectivos para implementar la RSC.

Palabras clave

Liderazgo responsable, Aspiraciones profesionales, Responsabilidad social corporativa, Gestión empresarial, Mentalidad de sostenibilidadKeywords

Responsible leadership, Professional aspirations, Corporate social responsibility, Business management, Sustainability mindsetCite this article as: Sánchez, F., Sandoval, A., Rodríguez-Pomeda, J., & Casani, F. (2020). Professional Aspirations as Indicators of Responsible Leadership Style and Corporate Social Responsibility. Are We Training the Responsible Managers that Business and Society Need? A Cross-national Study. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 36(1), 49 - 61. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a5

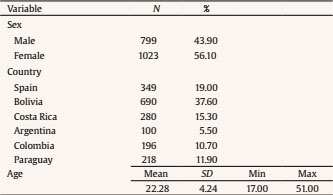

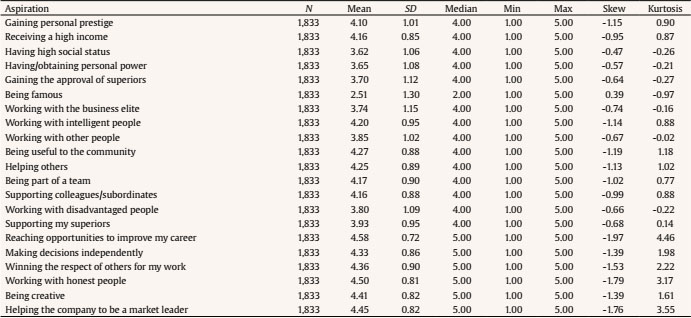

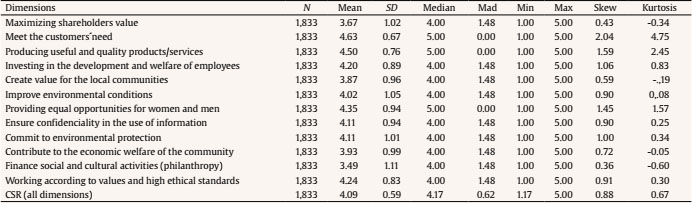

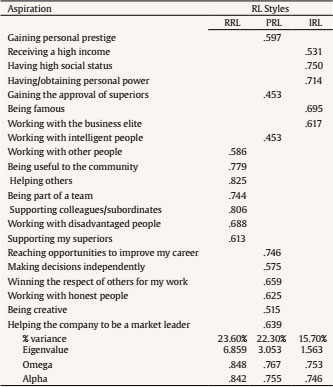

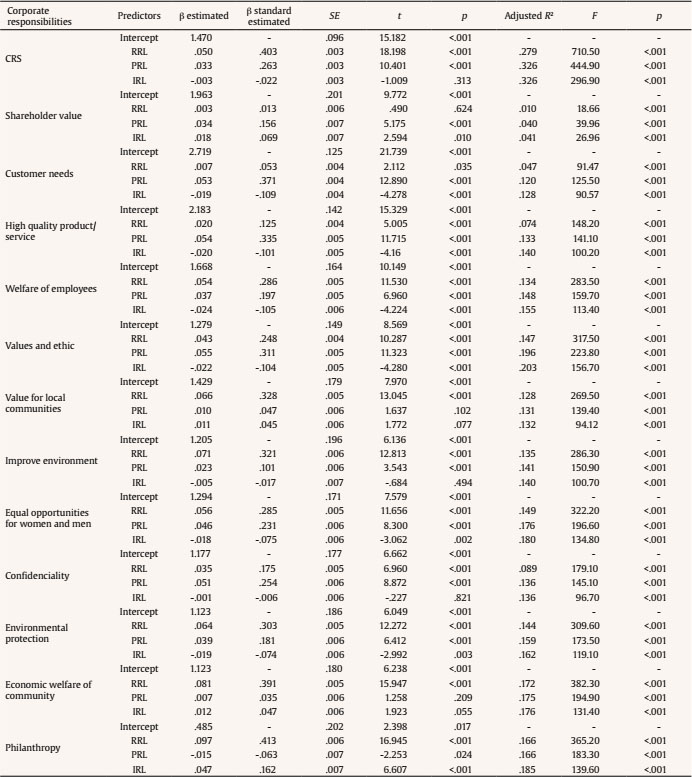

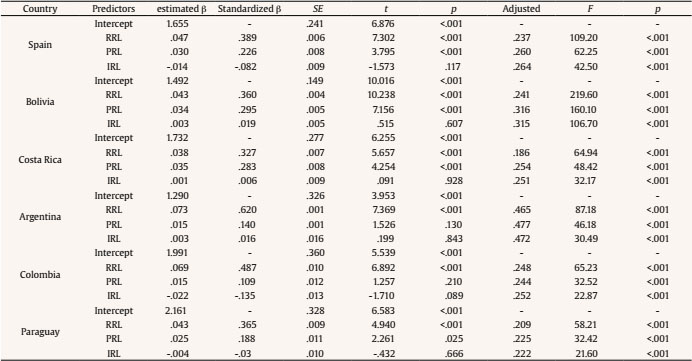

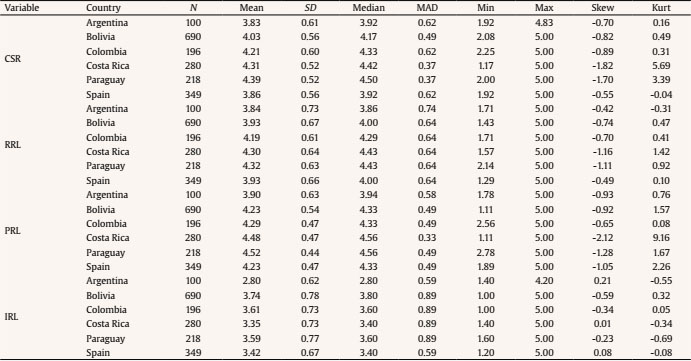

flor.sanchez@uam.es Correspondence: flor.sanchez@uam.es (F. Sánchez).The 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer revealed “a world of seemingly stagnant distrust” (Eldeman, 2018), with faith in all four key institutions (business, government, NGOs, and media) declining to levels lower than recorded since Edelman began tracking this trait among the general population in 2012 (https://www.edelman.com/trust-barometer). Citizen anger with these key institutions and their managers translates into demands for social responsibility from politicians, CEOs, managers, and employees. Business managers are faced with the challenge of leading in a complex and demanding environment, conditioned by a loss of trust attributable to years of greed-driven misconduct often associated with environmental disaster, financial scandals, and ruined lives. As such events have not been dislodged from the collective memory, business leaders are being questioned on ethical but also on professional grounds. To revert that climate, leaders individually and the companies they helm must prove themselves able to effectively protect the social and natural environment while at the same time turning a profit to contribute responsibly to social and economic welfare. Assumption of such responsibilities is in line with UN expectations around corporate participation in the achievement of its sustainable development goals (2030 SDGs). To that end, companies should seek to: a) improve the social and environmental conditions prevailing where they operate; b) eliminate any adverse impact on and enhance activities favoring company stakeholders; and c) design and develop innovative products and services in their respective industries. Such aims can be met by following the SDG Compass protocol (https://sdgcompass.org/). Responsibility is deemed to be a key element in effective leadership (see e.g.,Voegtlin, 2016; Waldman & Galvin, 2008). Responsible leadership (RL) can be viewed as an answer to society’s persistent demands for organizational responsibility. As a conceit, RL supplements other types of effective leadership, such as transformational, authentic or ethical, although with a twist, in that responsibility is deemed to lie at the core of effective management (Waldman & Galvin, 2008). From that standpoint, to be regarded as “responsible” a person must feel obliged to do the right thing toward others (Waldman & Galvin, 2008). In psychosocial terms, a person is held responsible for his/her behavior if it is perceived to be the cause of what happens to others (Heider, 1958). Responsibility can only be attributed to those with the motivation and capacity to behave in ways beneficial or detrimental to others. When this psychosocial definition of behavior is applied to managers, the assessment of their worth as effective and responsible leaders is based on the motivations or skills they are attributed. Against the backdrop of societal demands on business leaders, the RL concept can help link CSR and performance to policy makers’ and leaders’ actions (McWilliams & Siegel, 2011; Pless et al., 2012). Research on RL, spawned by research on corporate responsibility (Miska & Mendenhall, 2015), has both supplemented and consolidated its position in conjunction with its parent field. According to some authors (Voegtlin, 2011, p. 57), RL has narrowed the gap between the extensive research on CSR at the organizational level and the pressing need to address business leader responsibility. RL theory and practical application, in turn, stem from the change of focus in research on management and CSR. The move is away from macro-analysis and organizational variables (CSR configuration, business-society relations, etc.) toward micro-perspectives, zooming in on the effect that individual-scale management and leadership-related variables (values, skills, attitudes) have on CSR policy and practice (e.g., Aguinis & Glavas, 2012; Bies et al., 2007; Christensen et al., 2014; Devinney, 2009; Frynas & Yamahaki, 2016; Scherer & Palazzo, 2007, 2011). Society is demanding responsible managers able to re-establish the societal trust in business leaders lost as a result of the behaviors of certain “short-sighted bosses” who, from an instrumental perspective of CSR and stakeholder relations (Maak et al., 2016) and single-minded attention to the economic bottom line, consistently sought to maximize shareholder value, at times at the expense of all other stakeholders’ interests (Freeman et al., 2004, p. 366). The present authors believe that in such an environment, to recover public trust in the business community, companies and organizations in general and their leaders in particular must assume their responsibilities and apologize effectively (as described by Lewicki et al., 2016) for past untrustworthy behavior. In today’s context, senior managers must prove that they can meet strategic objectives, providing leadership built on integrity and ethical values along with business nous and deeming profits to be the result rather than the driver of value creation (Freeman et al., 2004). Stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984, 1994; Freeman et al., 2004), an inspiring area for RL research, assumes that values form a necessary and explicit part of conducting business and denies that business and ethics are separable (Freeman & Auster, 2011). In addition to abiding by business ethics, RL implies establishing relations with all stakeholders (Maak & Pless, 2006) and creating teams and communities in which everyone enhances the firm’s worth and value for stakeholders and for society (e.g., Baron, 2007). The notion of generating shareholder value is closely related to the idea of creating stakeholder value. Business is about implementing practice through which customers, employees, communities, managers, and shareholders consistently benefit over time. That approach acknowledges the importance of all potential stakeholders, including shareholders, in the organization’s sustainability. The authors of the theory stress the importance of considering the “legitimate interests of those groups and individuals [other than shareholders] who can affect or be affected” and “of investing in the relationships with those who have a stake in the firm” (Freeman et al., 2004, p. 365). Today’s CEOs must provide responsible guidance, be willing to play a more proactive role and initiate multiple stakeholder initiatives and technological innovations (Maak et al., 2016) to solve society’s complex problems and challenges as summarized in the 2030 sustainable development goals (2030 SDGs) such as environmental protection and sustainability, economic crisis, poverty, health, education, water scarcity, and immigration; in sum, inequalities between people, countries, and regions. One way to operationalize such initiatives is to integrate them into companies’ CSR actions. From the vantage point of outcomes, RL would be associated with the idea of economic, environmental and social sustainability and with the double (Miller et al., 2012) or triple (Elkington, 1997) bottom line, and act as a driver for attaining the 2030 SDGs. From a proactive perspective, the present authors believe that responsibility to society is a matter of concern not only for senior managers and CEOs presently running companies, but also for managers-in-training on university campuses the world over. The question posed is whether these future managers are in possession of the attitudes and values needed to provide the responsible and effective leadership required to implement the CSR policies and actions that create value in society and organizations and contribute to attaining the 2030 SDGs. The premise adopted here, which is consistent with the stance held by other authors (e.g., Voegtlin, 2016), is that a) RL can be defined as attitudes and values that denote a willingness to relate to and work in conjunction with internal and external stakeholders to effectively achieve strategic objectives and personal goals and b) RL can be inferred from an analysis of people’s behavior or their expected or intended behavior. Further to that premise, the paper pursues a two-fold aim: (1) to identify possible RL profiles or behavioral styles characterizing business school undergraduates by exploring their expectations around workplace behavior and achievement and (2) to analyze the relationship between RL style and the importance attached to CSR as a company responsibility. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The second section reviews the literature on issues related to the objectives and hypotheses. The methodology and research strategy adopted are described in the third section. The fourth explains the outcome of hypothesis testing. The fifth discusses the findings, their theoretical and practical implications and the conclusions. The limitations to the study and possible areas for further research are addressed in the final paragraphs. Theoretical Framework Responsible Leadership and Importance Attached to CSR Responsible leadership (RL). Responsible leadership is viewed as an emerging model based on new approaches to conducting business that could contribute to dispelling managerial mistrust. Depending on how it is practiced, however, it may foster or hinder the application of CSR (Christensen et al., 2014). Precedents for RL can be found in models of transformational or ethical effective leadership, with their similarities and differences (primarily as regards responsibility, as noted), neither of which is discussed here (for a review, see Voegtlin, 2011; Waldman & Galvin, 2008). RL has become a major item on academic and practical management agendas and has generated extensive literature on business management in recent years (e.g., Berger et al., 2011; Doh & Stumpf, 2005; Doh et al., 2011; Ketola, 2010; Maak & Pless, 2006, 2009; Maak et al., 2016; Pless et al., 2012; Siegel, 2014; Voegtlin et al., 2012; Waldman & Galvin, 2008). Despite the growing corpus of literature on responsible leadership, however, RL styles, the individual characteristics associated with RL (values, attitudes, behaviors), and especially the relationship between RL and CSR policy and practice are still poorly understood. Another conclusion drawn from a review of the literature is that most papers deal with theoretical issues; empirical data to support premises about the association between RL and CSR are scarce and based primarily on case studies. The result is a want of consistent and conclusive data. Further to Maak and Pless’ (2006) pioneering definition, responsible leadership is the art of building and sustaining good relationships with all relevant stakeholders (Maak & Pless, 2006, p. 6) although no consensus definition has been put forward (Maak et al., 2016). Nor has general agreement been reached about what RL entails, for that ultimately involves subjective assessment of behaviors (Maak et al., 2016; Waldman & Galvin, 2008). Moreover, actors and observers may assess behavior differently. As Pless et al., (2012, p. 52) note, some people may believe they act responsibly if they work to meet shareholder expectations (e.g., Siegel in Waldman & Siegel, 2008), whereas others measure responsible action in terms of corporate contributions to solving social problems (e.g., Freeman et al., 2004). Maak and Pless’ (2006) premise “responsible leadership as social connection” to be a milestone in RL research. Drawing from stakeholder theory with an ethical focus (Freeman, 1984, 1994; Freeman et al., 2004), Maak and Pless conceptualize RL as a “social-relational (Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Smircich & Morgan, 1982) and ethical phenomenon, which occurs in social processes of interaction” (Maak & Pless, 2006, p. 99). RL is the result of interaction between a leader and a broader group of followers in- and outside an organization in which the leader-follower model is replaced by a leader-stakeholder relationship (Doh & Quigley, 2014; Maak et al., 2016; Voegtlin et al., 2012). RL is the outcome of personal interdependence in which the actions of all involved contribute to the final result. The followers are in fact stakeholders, insofar as they are affected by the leader’s actions. At the same time, however, they play a significant role in the leadership project, in which they participate on equal or unequal standing with the leader. Thus conceived, RL is not merely another form of leadership but an essential part of leadership (Voegtlin, 2016, p. 585), a process closely associated with social interaction and interpersonal relationships. Interpersonal relations are imperative to leadership. Roland Pellegrin contended as much early on, highlighting the importance of social relationships in a paper on leadership published in the nineteen fifties (Pellegrin, 1953). In synthesis, the foundational idea on which our study is built is that the personal values and attitudes indicative of a willingness to relate to and work with others, including internal and external stakeholders, constitute the fundamental, overarching dimension that defines and is requisite to RL. Acknowledgement of this fundamental relational dimension and analysis of the results of interaction and connectedness with stakeholders have inspired a great deal of RL-related research (e.g., Doh & Quigley, 2014; Maak & Pless, 2006, 2009; Maak et al., 2016; Miska et al., 2014; Miska & Mendenhall, 2015; Pless & Maak, 2011; Stahl & De Luque, 2014; Voegtlin, 2016; Voegtlin et al., 2012). Likewise, enlightening in the context of the relational element that defines RL and with respect to the aims of this study are the proposals put forward by Maak & Pless (2006, pp. 100-101) on the roles assumed by responsible leaders with different stakeholders. With employees, such roles include mobilizing people and teams to achieve company objectives, providing support, behaving ethically in the pursuit of objectives, encouraging cooperation in- and outside the organization, ensuring safe, healthy and non-discriminatory working conditions and fair and equal employment opportunities regardless of sex, age, nationality, etc. In their relations with clients and customers, responsible leaders seek to meet needs and ensure the safety of company products and services. In terms of the social and natural environment, RL entails the adoption of eco-friendly production, the use of renewable resources, material recycling, and energy efficient procedures. RL also encourages active support for the well-being of the social and economic communities where companies conduct business. Responsible leaders likewise protect and seek a suitable return on shareholders’ capital investment (Maak & Pless, 2006; Maak et al., 2016). In line with the stakeholder perspective, in assuming these responsibilities companies and managers must deem shareholders to be stakeholders to establish a balance among all concerned and favor long-term corporate sustainability (Freeman, 1984; Freeman et al., 2004). Despite the paucity of empirical studies on RL, a number of behavior-based classifications of responsible leadership styles in organizations has been proposed (Pless et al., 2012; Waldman & Galvin, 2008, among others). Maak et al. (2016) recently proposed a theoretical framework based on a synthesis of these styles to explore the micro-foundations of CSR. Further to earlier studies and observations, those authors propose two styles of RL, integrative and instrumental. They are described as differing in the values that transcend specific situations and lead to desirable end states or behaviors (Schwartz, 1994) and in CSR policy- and practice-related behavioral patterns. The integrative RL style is characterized by a stakeholder-geared social or relational approach focusing on business and societal objectives and a high degree of interconnectedness (interactions with a broad spectrum of internal and external stakeholders). This style seeks the cooperation and integration of the organization’s various stakeholders, whose networking favors inter-stakeholder communication, collaboration, and alignment. Their participation in decision-making is also encouraged to lay the grounds for processes combining the interests and demands associated with pro-social, cost-benefit logic. Instrumental responsible leadership, in turn, is characterized by an actor-centered perspective that pursues the maximization of shareholder value by focusing on the economic bottom line; scant interconnectedness (minimal interaction with a small group of internal stakeholders); a single-minded approach to employees and external stakeholders, directing their skills to the attainment of the organization’s goals; and the general application of selective, economic means-end relationships confined primarily to those able to contribute in some significant way to the achievement of objectives (i.e., who have the power to grow profits). These premises about the effect of RL style in establishing the thrust of CSR policy are theoretical; the scant empirical data furnished in their support is drawn from case studies (e.g., Maak et al., 2016; Pless et al., 2012) affording no conclusive evidence. To the best of the present authors’ knowledge, no analysis has yet been conducted of future managers’, i.e., business management undergraduates’, RL styles. This review of the literature suggests the two premises addressed in this article. The first is that RL is a behavioral workplace style associated with certain values (Aygün et al., 2008; Schwartz, 1994) and attitudes. The second, which follows from the first, is that the direction adopted by RL can be matched to observable workplace relations and behaviors. RL may, then, be identified by observing actors’ actual or potential workplace relationships, behaviors and performance or, where that is not feasible, their intended behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). The indicator for intended behavior used in this study was students’ workplace aspirations. This study aimed to identify personal aspirations or anticipated workplace behavior patterns among business school undergraduates that could be associated with RL styles. The criterion used was the aspiration to relate to or work with others or to pursue more individualistic goals. Hypothesis 1: Professional aspirations associated with the desire or intention to relate to and cooperate with workmates would denote relational responsible leadership and the pursuit of essentially personal interests individualistic responsible leadership, both as described in the literature. Importance attached to CSR. CSR, an elusive construct, evolved from the notion of general CR put forward in the nineteen fifties (Carroll, 1999), today likened to sustainability (Carroll, 2015). The definitions of CSR in place normally refer to the environmental and social responsibilities assumed by organizations in connection with the stakeholders affected by their activities, above and beyond legal requirements (Freeman, 1994). CSR has also recently acquired significance in connection with the UN’s 2030 SDGs calling for business engagement. The literature reviewed includes many analyses of different groups’ perception and assessment of and attitudes toward CSR. Many of those studies focus on business students. Deploying similar methods, several studies have analyzed such future managers’ attitudes toward or perception of the responsibilities involved in CSR in places such as the US (Aspen Institute, 2002, 2008; Kolodinsky et al., 2010; Ng & Burke, 2010; Wong et al., 2010), Europe (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Lämsa et al., 2008; Matten & Moon, 2004; Zopiatis & Krambia-Kapardis, 2008) China (e.g., Wang & Juslin, 2011) and Asia (Murphy et al., 2016). No such studies involving Ibero-American students have been conducted, however. Although with some differences, the results generally reveal business students’ concern about CSR issues, a growing perception of CSR as part of a company’s responsibility as their management training progresses, and their high regard for what may be deemed to be stakeholder theory, given their positive view of relations with groups other than shareholders. (For a detailed review of these studies see, e.g., Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015). The implementation of corporate responsibility or sustainability depends on the values and ideologies that shape an organization’s culture and the specific leadership style and management it fosters (Doh & Quigley, 2014; Doh et al., 2011; Filatotchev & Nakajima, 2014; Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010; Stahl & De Luque, 2014). Leaders are assumed to be decisive in the implementation of CSR. The model proposed by Carroll (1979) defines the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary dimensions of company and manager responsibilities to society. As noted, a certain initial inattention to the association between business managers’ role and CSR (Orlitzky et al., 2011, p. 3) has been followed by the desire, which has grown along with interest in RL, to understand the relationship between responsible leadership and the definition and implementation of CSR policy. That interest is informed by the conviction that the daily behaviors and strategic plans of responsible leaders can foster specific CSR and sustainability policies that enhance organizations’ performance (Maak & Pless, 2006; Pless et al., 2012; Waldman, 2011; Waldman & Galvin, 2008). A deeper understanding is needed, however, of how and when responsible leadership affects the CSR policies and practices prioritized by managers (Christensen et al., 2014; Maak et al., 2016). Maak et al. (2016), in one of the few papers that have advanced the study of the relationship between RL and CSR, contend that in light of the values underpinning RL styles, an integrative leadership style would be based on the actor’s perceived moral responsibility to stakeholders. In contrast, instrumental responsible leadership is based on a moral responsibility to shareholders. Behaviorally speaking, the former would translate into a higher regard for organizations’ and managers’ responsibilities to stakeholders and the latter for their responsibilities to shareholders. Other authors report that RL styles (integrative or instrumental) can be correlated to organizations’ engagement with CSR, although their conclusions are based primarily on case studies and qualitative methods. In a qualitative study, Pless et al. (2012), for instance, analyzed 25 business leaders’ and entrepreneurs’ personal visions of CSR implementation. Voegtlin (2016, p. 491), in turn, proposed four dimensions of responsibility for understanding RL, backed by qualitative data from interviews with company managers and NGO representatives. Some authors acknowledge the want of validation of their premises and the existing research on the relationship between RL and CSR is generally agreed to be insufficient (Christensen et al., 2014; Doh & Quigley, 2014). In a nutshell, no conclusive data have yet been published on how RL styles can affect the importance attached to furtherance of CSR in companies. To the authors’ knowledge, the possible relationship between business students’ RL style and their thoughts on company responsibility in furthering CSR has not been studied. This article consequently analyzes the relationship between possible RL styles, as inferred from participants’ behavior and professional aspirations, and the importance attributed to companies’ responsibilities to their several stakeholders and the social and environmental dimensions of CSR. The second hypothesis addressed is as follows: Hypothesis 2: Significant differences exist between how CSR responsibilities are regarded, depending on the actor’s RL style. The more closely aspirations and intended conduct are aligned with relating to others and working to meet their needs, the greater the importance attached to CSR is. The assessments performed in the six countries participating in the study around the importance accorded CSR depending on leadership style are also analyzed. In the absence of prior studies on the subject, this paper constitutes an exploratory analysis of that relationship. Participants and Procedure The data were collected as part of an international research project funded by the Center for Latin American Studies (see Casani et al., 2015, p. 126). The hypotheses were tested by surveying 1,833 first- or second-year business management students enrolled in six Ibero-American universities (see Table 1) between September 2015 and May 2017. The participants had received no specific leadership or CSR training. With a mean age of around 22, these Generation Y (1982-2000) men and women will soon be shouldering responsibility for the planet, business, and society. Data were collected in each country by a project researcher from that country in accordance with a common protocol. After the researcher briefly explained the research objective and committed to handling, storing, and sharing the research data confidentially, participants granted permission for its use for research purposes only. They subsequently completed the questionnaires in writing in a classroom context at their universities over a 15 to 20 minute period. Respondent demographics were collected in a final section of the questionnaire. Subjects were not granted credits for their participation. Compliance with the universities’ ethical guidelines on data obtained from human beings was guaranteed. The characteristics of the populations are summarized in Table 1. Table 1. Sex, Nationality and Age of Sample Participants   Note. There are 11 missing values in sex. There are 179 missing values in age. Instruments Measure of leadership style. In keeping with the aforementioned literature, business school undergraduates’ RL style was identified by exploring their personal aspirations and intended workplace behavior based on a scale proposed by Aygün et al. (2008) and used in previous studies (e.g., Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Alonso-Almeida et al., 2017). Participants were asked to specify the extent to which they agreed that the aspirations or behaviors described in 21 statements would be within their reach in the course of their careers. Table 2 lists the items and scores on the questionnaire used in this study, the internal consistency (= reliability) of which was estimated to be α = .76, ω = .82. Table 2 Participants’ Professional Aspirations: Statistical Descriptors   Note. Scale ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) Measure of CSR. CSR dimensions were assessed on the grounds of questions adapted from the original Aspen Institute questionnaire and used in similar studies by Lämsa et al., (2008) and Alonso-Almeida et al. (2015, 2017), to name a few. Participants in the study described here were asked to rank the importance of each of 12 CSR corporate responsibilities on a five-point Likert scale (1 = unimportant to 5 = very important). The items and their valuation are given in Table 3. In this case internal consistency was α = .86 and ω = .87. Table 3 Importance Attached by Participants to CSR Dimensions: Statistical Descriptors   Note. Scale ranges from 1 (not important) to 5 (very important); CSR = corporate social responsibilities. Data Analysis Descriptive analyses were conducted of all the variables included in the study. The first of the two steps followed to verify the working hypotheses entailed analyzing and selecting the behaviors and aspirations associated with possible RL styles. The procedure involved exploratory factor analysis based on polychoric correlation, non-weighted least squares, parallel analysis to ensure a constant number of factors, and oblimin rotation. In the factor analysis, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test was used to measure sampling adequacy (.94); Barlett’s test of sphericity was used for the factor decision (χ2 = 39,618.50, df = 1,891, p < .001). All the model variables were Box-Cox transformed prior to regression analysis. Ordinary least squares regression was conducted to test the percentage of variation in RL style and items explained by the CSR scores and factors. Regression analysis was also performed country-by-country. R statistical software (R Core Team, 2019) and the psych (Revelle, 2019) and lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) libraries were used for all the analyses, the results of which are set out in the following section. The significance level was .05 throughout. The results are discussed below under three headings. The first addresses the leadership style of the sample as a whole and the second the inter-style differences in the importance attached to CSR-related company responsibilities. The third analyzes the importance attached to CSR by students adhering to each RL style in the six participating countries. RL Styles Factor analysis was performed in pursuit of a possible classification of aspirations that could inform different RL styles. The findings showed that three main groups of variables or factors can be identified, each comprising a separate profile of aspirations for personal achievement that could be associated with the RL styles proposed in the literature. The first profile exhibited a prevalence of expected workplace behaviors and achievements associated with a willingness to relate to and work with others (internal consistency α = .84, ω = .85), which accounted for 23.6% of the variation. In that profile, the achievement-based items included performing professional tasks jointly with others – “help others” (.82), “support colleagues/subordinates” (.81), “be useful to the community” (.78), “form part of a team” (.74), “work with socially disadvantaged people” (.69), “support my superiors (.61), and ”work with others” (.59). The second factor or profile consisting of reaching personal professional and organizational goals and only working with certain types of people (internal consistency α = 75, ω = .77) accounted for 22.3% of the variation. In that profile, the achievement-based items included “reach opportunities to improve my career” (.75), “win the respect of others for my work” (.66), “help the company to be a market leader” (.64), “work with honest people” (.62), “gain personal prestige” (.60), “make decisions independently” (.58), “be creative” (.51), “gain the approval of superiors” (.45), and “work with intelligent people” (.45). The third profile, characterized by an individualist, earnings-focused bent, a paucity of personal relationships and scant social interaction (internal consistency α = .75, ω = .75), accounted for 15.7 % of the variance. The items at issue were associated with individual achievements: “social status” (.75), “personal power” (.71), “being famous” (.70), “work with the business elite” (.62), and “earn a high income” (.53). That profile would match an individualist RL style. The factor loadings for the three profiles are given in Table 4. Table 4 Factor Analysis for RL Styles Based on Professional Aspirations   Note. Responsible Leadership (RL) style: RRL = Relational RL; PRL = Pragmatic-Instrumental; IRL = Individualistic. These findings supported the assumptions underlying hypothesis 1, revealing three separate behavioral profiles that could be associated to different degrees with the socio-relational dimension proposed in the literature to define responsible leadership (e.g. Maak y Pless, 2006; Pless et al., 2016). Further to the data collected for this study, these styles are referred to hereafter as the “relational” (RRL), “pragmatic”-instrumental (PRL) and the “individualist” (IRL) styles of responsible leadership. RL Styles and Importance Attached to CSR All 12 corporate responsibilities related to CSR, ranked in Table 3 by score, were deemed by participants to be important, for all responsibilities were accorded values higher than the scale mid-point. The scores for the items ranged from 4.63 (“meet customer needs”) to 3.49 (“finance social and cultural activities”). The second hypothesis was tested with and supported by OLS multiple linear regression analysis (Table 5). The analyses conducted showed a closer correlation between the relational responsible leadership (RRL) style (standardized β = .40, p < .001, R2 = .28) and the pragmatic-instrumental responsible leadership (PRL) style (standardized β = .26, p < .001, R2 = .33), and the belief that fostering CSR are important company responsibilities. No significant general relationship was observed between individualist RL and a high regard for CSR. Table 5 RL Style and Importance Attached to CSR Dimensions: OLS Multiple Linear Regression Analysis Values   Note. Responsible Leadership (RL) Style: RRL = Relational RL; PRL = Pragmatic-Instrumental; IRL = Individualistic. More specifically, subsequent regressions showed that the relational RL style was directly correlated to corporate social responsibilities associated with local community well-being: “contribute to the economic welfare of the community” (standardized β = .39, p < .001), “create value for the local communities where the company operates” (standardized β = .33, p < .001). A third measure, “fund social and cultural activities or engage in philanthropy” (standardized β = .41, p < .001), also formed part of the individualist RL style. Both the relational and pragmatic-instrumental RL styles, albeit to different extents, were directly correlated with stakeholder well-being: “invest in employee training and welfare” (respectively, standardized β = .29 and β = .20, p < .001) and “equal opportunities for women and men” (respectively, standardized β = .28 and β = .23, p < .001). Both also correlated to environmental protection: “commit to environmental protection” (respectively, standardized β = .30 and β = .18, p < .001) and “improve environmental conditions” (respectively, standardized β = .32 and β = .10, p < .001). Ethical behavior was another area where they exhibited correlation: “behave in keeping with values and high ethical standards” (respectively, standardized β = .25 and β = .31, p < .001) and “ensure confidentiality in the use and transfer of information” (respectively, standardized β = .17 and β = .25, p < .001). RRL and PRL, particularly the latter, were correlated to running companies “to meet customer needs” (respectively, standardized β = .05 and β = .37 p < .001) and “high quality of product/service (respectively, standardized β = .12 and β = .33, p < .001). In contrast, both the pragmatic and individualist RL styles were directly correlated to corporate social responsibilities associated with maximizing shareholder value (respectively, standardized β =.16, p < .001 and β = .07, p < .01). The individualist RL profile was visibly un- or even negatively correlated with all the major responsibilities associated with organizations’ internal and external sustainability: customer needs, product/service quality, employee welfare, ethical behavior, equal opportunities for women and men, confidentiality, or environmental protection. Table 6 RL Style and Importance Attached to CSR Dimensions by Country: OLS Multiple Linear Regression Analysis Values   Note. Responsible Leadership (RL) Style: RRL = Relational RL; PRL = Pragmatic-Instrumental; IRL = Individualistic. Those findings generally supported hypothesis 2. The scores for company responsibilities predicted on the grounds of leadership style are shown in Table 6. Regard for CSR by Country The descriptive analyses for the major variables are given by country in Appendix. In keeping with the stated aim, specific regression analyses were conducted on the importance attached to CSR by each leadership style in each participating country. The findings revealed inter-country differences as well as differences between single countries and the overall results. In Bolivia, Costa Rica, Paraguay, and Spain, the relational RL style and to a lesser extent the pragmatic-instrumental style predicted a higher regard for CSR as one of an organization’s key responsibilities. In Colombia and Argentina only the relational style predicted a significantly positive view of CSR. The individualist style was not significantly associated with a high regard for CSR in any of the participating countries or in the sample as a whole. The premise initially assumed was that responsible leadership (RL), like any other type of leadership, can be defined by behavior, or the behavior and aspirations, as informed by individuals’ values and attitudes. The data supported the first working hypothesis to the effect that participants’ self-perception, the achievements they deem within their reach and their intended workplace behaviors reveal three distinct leadership styles. The first, relational RL, is characterized by a willingness to interact and work with internal (colleagues, subordinates, bosses) and external (community, socially disadvantaged people) stakeholders. It is an enhanced form of the socio-relational dimension associated with RL in the literature reviewed (e.g., Maak & Pless, 2006; Pless et al., 2016). On the opposite extreme, individualist RL aspires to personal advancement and aims to achieve economic objectives with a scant willingness to establish personal relationships. In-between, the pragmatic-instrumental profile (PRL) seeks personal objectives for professional advancement in pursuit of company goals (such as industry leadership). On the whole, the findings support working hypothesis 1. The data attested to the existence of these three patterns, two of which can be equated to the leadership styles proposed by Maak & Pless (2006) while the third combines features of both. The second objective was to furnish empirical evidence to support theories relating RL style to CSR, for which little quantitative data has been forthcoming to date. That aim was pursued by analyzing the correlation between RL style and classical CSR dimensions defined as organizations’ essential responsibilities to stakeholders, the environment, and society. The findings showed that on the whole, the business school undergraduates (managers in training) surveyed deemed CSR dimensions to be very important corporate responsibilities. They also showed that although all the dimensions were regarded as important organizational responsibilities (all scored higher than the scale mid-point), participants ranked responsibilities geared to stakeholder (employees, clients, superiors, etc.) well-being to be companies’ primary responsibilities, ahead ( in descending order) of their responsibilities to the environment, society, and shareholder value. Overall, undergraduates were more inclined to support the stakeholder (Freeman et al., 2004; Freeman, 1994) than the shareholder (Friedman, 1970, 2007) perspective, attaching lesser importance to shareholder value. Those findings are consistent with results reported in previous studies, such as Alonso-Almeida et al. (2015). Significant differences were observed between RL styles, however. The data showed that the more closely aspirations and workplace behavioral intentions were associated with relating to and working with others and concern for circumstances beyond the immediate surrounds, the greater the importance attached to CSR as a company responsibility, as proposed in working hypothesis 2. Those whose replies aligned them with the relational or pragmatic RL style exhibited a higher regard for CSRs geared to local community and internal and external stakeholder well-being, and environmental protection. Both, particularly the latter, also had a positive view of ensuring business sustainability by, for instance, meeting customers’ needs, seeking to ensure product/service quality and behave ethically. Such attitudes concurred with the integrative vision attributed to RL by some authors (e.g., Freeman et al., 2004; Waldman & Galvin, 2008), who premise that the stakeholder perspective is both compatible with and strikes a balance between good economic management and defense of company interests (double bottom line), ensuring business sustainability. The country-by-country analysis of the importance attached to corporate social responsibility by leadership style revealed that four of the six countries followed the overall pattern, with the relational and pragmatic leadership styles attaching importance to CSR and its dimensions as a company responsibility, whereas in Argentina and Colombia that attitude was exhibited by the relational style only. On the whole, aspirations and intended behaviors geared toward personal relations were the attitudes most closely aligned with a high regard for CSR. One very categorical finding was the disconnect or absence of association between the individualist RL style and CSR, which was consistent with reports by earlier authors, such as Maak and Pless (2016). Nonetheless, as an initial approach to the issue, this study must be followed up by further exploration into these relationships. The findings for the sample as a whole and by countries do not provide a wholly affirmative answer to the question: are we training the responsible managers that business and society need? When managers in training are observed to be characterized by aspirations and intended behavior in which contributing to community value, ensuring employee well-being and equality, protecting the environment and behaving ethically are deemed to be major company responsibilities, the system can be said to be training managers with the attitudes and values required to drive CSR from within companies. These future leaders may consequently be counted on to contribute in the immediate future to attaining the SDGs for which companies bear co-responsibility. That the data also revealed the existence of individualist profiles is a cause for concern, however, for such attitudes are associated with a disconnect from or animosity toward CSR and a negative view of the importance of factors contributing to organizations’ sustainability. Students exhibiting such aspirations and values could not be counted on to pursue the 2030 SDGs calling for business and company manager participation. Leadership styles are normally and primarily studied to establish their possible relationship to an individual’s competence for certain tasks or to meet certain objectives: in this study, the ability to foster CSR. The findings suggest that the relational or the pragmatic RL style propels CSR more effectively, insofar as its practitioners would meet the classical leadership criteria defined in the literature (e.g., Blake & Mouton, 1964; Fiedler, 1967) as imperative to efficacy: an interest in people and their needs and in the essential tasks that ensure compliance with organizational objectives and business sustainability (e.g., by meeting customers’ needs). A relational or pragmatic RL style informed by this double bottom line perspective would most effectively further CSR policy and practice. Nonetheless, drawing again from the teachings of leadership research, a given RL style does not alone suffice to ensure the best CSR policies and practices are encouraged. Managers’ decisions and actions are known to be contingent upon organizational, social, and cultural factors that may call for a variety of strategies. Leaders’ efficacy depends on the leeway afforded by a given situation: legislative requirements and stakeholder behavior (greater or lesser sensitivity to CSR and SDGs), for instance, may limit the impact of their management decisions. Although the matter calls for further study, the business contexts in which CSR policy and practice are to be carried through may be thought to be characterized by a medium level of definition (the need to prevent the adverse effects of business activity on people and the environment is acknowledged, but the knowledge required to do so is not always in place). Building on classical leadership research (e.g., Blake & Mouton, 1964; Fiedler, 1967), in such situations a medium degree of structure associated with the relational RL style could be inferred to most effectively spur CSR. The empirical evidence (specific data for a sizeable sample) furnished by this study contributes to the understanding of RL and its relationship to regard for CSR from what appears to be an unexplored vantage point. The results are encouraging, for they suggest that today’s managers in training will act responsibly after earning their degrees and contribute to attaining the 2030 SDGs although an “older” mindset also appears to persist that is ill-aligned with the needs of today’s society and companies. Many authors express concern that business education fails to teach undergraduates to confront the challenges entailed in ethical and responsible management (see Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015; Arruda Filho et al., 2019). Scholars addressing the subject seem to agree to the need to change that older mentality and encourage knowledge and attitudes that will redound to responsible future leadership. The consensus deduced from the literature is that leadership, like an understanding of sustainability, can be learned. Consequently, if some students fail to spontaneously adhere to the leadership style that can most effectively further CSR policy and practice (as observed in this study), business management curricula should include specific content from the outset to induce the acquisition of leadership styles more in keeping with the needs of twenty-first century companies and society. Authors such as O’Sullivan (2017) advocate for a change of mindset and the institution of an educational model that includes sustainability training to help students develop skills favoring relations and communication with peers and staff. They should also be encouraged to participate in university affairs, gain a deeper understanding of global issues, and assume the responsibilities incumbent upon them. Aware of the need to wed public and private efforts and further cooperation between academia and civil society, the UN has undertaken certain initiatives to spotlight the world’s most pressing problems. Its Global Compact, for instance, seeks company engagement with CSR and the SDGs, whereas its Principles for Responsible Management Education (UN PRME) pursue changes in management and leadership training. Educational projects that have assimilated these initiatives as a reference have reported progress in developing a new sustainable leadership mindset, although for the time being the evidence is based primarily on case studies conducted in private business schools (e.g., Arruda Filho et al., 2019; O’Sullivan, 2017). Along these lines, Arruda Filho et al. (2019) analyzed the effects of an educational project implemented in a Brazilian business school addressing sustainable development and globally responsible leadership, among others. The data showed a significant variation in students’ average understanding of the conceits on which a sustainability mindset builds (SDGs, environmental footprint, UN PRME, Global Compact, sustainable development, learning community). The study did not analyze the relationship between that understanding and future attitudes and conduct, however. Education for sustainable development (ESD) has been fostered not only in the context of business studies, however. Organizations such as the UN also seek to heighten citizens’ sustainability competence by integrating ESD principles into all aspects of education and learning and encouraging change in knowledge, values, and attitudes. The aim is to foster behaviors in keeping with societal demands on undergraduates as citizens and future professionals. In practice, implementing such programs poses economic and cultural challenges in all stages of education, lifelong learning included (Holm et al., 2016). As most executives entrusted with managing society’s institutions train at higher education institutions (HEIs), universities bear the brunt of the responsibility for raising awareness of the sustainability issue. It is incumbent upon them to disseminate the knowledge, technologies, and tools required to ensure an environmentally sustainable future by offering sustainability training for successive cohorts of enrollees in all manner of studies. The present review of the literature revealed considerable progress in the inclusion of sustainable development questions in HEI curricula, with European institutions spearheading the trend (see the review by Lozano et al., 2019). Research on SD skills and the pedagogical approaches best suited to developing them has contributed to such progress. By way of example, Lozano et al. (2019) recently analyzed the relationship between skills developed and pedagogical methodology based on the results of a survey among 390 educators from 30 European higher education institutions who were queried about the sustainability content of their courses, the competence developed, and the pedagogical approaches used. Although they must be viewed cautiously in light of the nature and composition of the sample, the findings showed that the social dimension of sustainability was addressed less fully than economic and environmental issues. The authors observed that some of the skills most closely associated with relational RL, such as interpersonal relations and collaboration, were among the least intensely developed. They also concluded that such skills were most effectively assimilated when students worked on projects or were exposed to problem-based learning. The content and methodologies best suited to developing and measuring university students’ sustainability competence still constitute a moot point, however. Limitations and Future Research This initial attempt to empirically study the relationship between the RL style expected according to business undergraduates’ aspirations as managers in training and their regard for CSR and the 2030 SDGs raises other questions that might be addressed in future studies. One limitation of this study would be that it is based on the intention to behave in given ways or achieve certain objectives but not on observed conduct. While the initial assumption was that responsible leadership can be identified by observing workplace relationships and behaviors, the respondents in this study had not yet acquired work experience. Nonetheless, one generally accepted principle in behavioral science is that attitudes and intentions are reliable precedents for actual behavior and can predict how people ultimately act (Ajzen, 1991; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). That notwithstanding, longitudinal or supplementary studies analyzing actual behavior should be conducted. People with professional aspirations that can be associated with more relational responsible leadership would be expected to exhibit “greener” and more socially responsible behavior than those identifiable with a more individualistic RL style. Those very correlations were found in an analysis of behaviors attributable to ethical leadership (Roeck & Farooq, 2018), which is not very different from the responsible leadership addressed here. In another vein, the reliability and validity of professional aspirations as an indicator of the leadership style to be implemented by future professionals, which is essential to the research discussed here, would have to be ensured by surveying business students who have trained for sustainability and responsible leadership. The aim would be to determine whether after exposure to such training students express aspirations and attitudes geared more to responsible leadership (relating to and working with others) than to individualistic expectations and attitudes (money, fame) so characteristic of millennials, according to some studies (see for instance Massachusetts General Hospital’s Laboratory of Adult Development data: https://www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/research/laboratory-of-adult-development). A need is also felt to ascertain whether, as suggested by previous research, more than one responsible leadership style may coexist in the same person. (This item is likewise on the RL research agenda: see Waldman & Balven, 2014). An understanding of the factors that favor the simultaneous or sequential implementation of different RL styles should be explored, along with their effectiveness in handling contextual demands. The effect of context in itself constitutes an issue that merits full research attention in responsible leadership studies. Some authors even suggest that CSR policies may impact employee behavior in terms of social responsibility (Erdogan et al., 2015; Roeck & Farooq, 2018). Further analysis is also required of the factors that may explain the inter-country differences observed in the regard for CSR. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgments The authors wishes to thank Maite Camacho for reviewing the paper, Mercedes Ovejero for assisting with the statistics, and Margaret Clark for editing the manuscript. Cite this article as: Sánchez, F., Sandoval, A., Rodríguez-Pomeda, J., & Casani, F. (2020). Professional aspirations as indicators of responsible leadership style and corporate socialresponsibility. Are we training the responsible managers that business and society need? A cross-national study. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 36(1), 49-61. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a5 References |

Cite this article as: Sánchez, F., Sandoval, A., Rodríguez-Pomeda, J., & Casani, F. (2020). Professional Aspirations as Indicators of Responsible Leadership Style and Corporate Social Responsibility. Are We Training the Responsible Managers that Business and Society Need? A Cross-national Study. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 36(1), 49 - 61. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2020a5

flor.sanchez@uam.es Correspondence: flor.sanchez@uam.es (F. Sánchez).Copyright © 2025. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef